Hope you'll join us over at the new place: www.picklemethis.com. Please change your links accordingly.

Hope you'll join us over at the new place: www.picklemethis.com. Please change your links accordingly.

Monday, February 15, 2010

Moving Day!

Hope you'll join us over at the new place: www.picklemethis.com. Please change your links accordingly.

Hope you'll join us over at the new place: www.picklemethis.com. Please change your links accordingly.

Friday, February 12, 2010

Books I found in various boxes along the sidewalk on my walk home from Kensington Market

1) If Life is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I Doing in the Pits by Erma Bombeck. 2) Break, Blow, Burn by Camille Paglia. 3) Lost Girls by Andrew Pyper (personally autographed to boot, with many thanks, but I won't say to who). 4) hardcover of What is the What by Dave Eggers. 5) Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations by Georgina Howell

1) If Life is a Bowl of Cherries, What Am I Doing in the Pits by Erma Bombeck. 2) Break, Blow, Burn by Camille Paglia. 3) Lost Girls by Andrew Pyper (personally autographed to boot, with many thanks, but I won't say to who). 4) hardcover of What is the What by Dave Eggers. 5) Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations by Georgina Howell

Why I love people...

"The idea grew as Morrison considered ways to make the cake pans fly better..."

From the obituary of Walter Morrison, who invented the frisbee.

From the obituary of Walter Morrison, who invented the frisbee.

Thursday, February 11, 2010

Why I have business in the bedroom of Adam Giambrone

I don't know if there are two things I like more than passing judgement and reading stories, and so I've been wholly absorbed by the perils of Adam Giambrone this week. I've long had my eye on the guy, if only to use his surname as verb in various contexts, which is always funny when I'm overtired, and so I've been paying attention since Monday, however much that's less than high-minded to admit.

I don't know if there are two things I like more than passing judgement and reading stories, and so I've been wholly absorbed by the perils of Adam Giambrone this week. I've long had my eye on the guy, if only to use his surname as verb in various contexts, which is always funny when I'm overtired, and so I've been paying attention since Monday, however much that's less than high-minded to admit.I've been paying attention because I'm a follower of plot, of twists and turns, and wild leaps. Office couches, text messages, denials then tears at the press conference. The scintillating details, the text messages, and we're not supposed to care because it's his private life after all, but don't you care just for that reason? The kind of access to private lives that we usually have to read novels for, and perhaps it's why we read novels anyway. How can you turn away from it? I can't.

Of course, there are real people involved, real lives at stake. To which I posit that there aren't. Case in point, the picture above from The Toronto Star-- have you ever seen a more calculated chemistry? I could say I'm sorry for the wife, but I wouldn't really mean it. To pretend otherwise would be disingenuous. Giambrone himself has become a fiction, has probably long been one, but we know it now. If he were less lame, he'd be Jay Gatsby. And of course, there's a real Giambrone still deep down inside him, but that's not the guy upon whom I'm passing judgement.

The guy upon whom I'm passing judgement is an idiot. Not only does he think that women are disposable, but he dates the kind of woman who wouldn't hesitate to destroy his whole career in a heartbeat. The kind of woman who'd date him even though she thinks he lives with his parents, and he's 32. And-- though this population is larger than I'd initially suspected -- he dates the kind of woman who'd tolerate that haircut. He gets caught, and he lies about it. He someone who knows himself better than anyone else knows him and yet he sets himself up for this exact situation by pursuing public life (which, let's face it, most people don't do for really honorable reasons). Even the smartest guy would have trouble balancing his public face with a life that's a lie.

I'm not condemning Adam Giambrone for immorality, for that kind of thing is always a little bit subjective, but I think I'm allowed to call it as I see it-- he's an idiot.

I hate the word "peccadillo". Why do women never get to have those? A "peccadillo" trivializes all manner of sins, packs them up in a neat valise that rhymes with armadillo, and how convenient is that? And then someone will lecture me about casting first stones, but these guys get up to the kind of wrongdoing I'd never consider. I know I'm young, but I'm getting older every day, and I remain steadfast about this. And to suggest that I'm just naive then is an insult to men of integrity everywhere, and I've met an awful lot of these in my life. I just think we all deserve a lot better.

Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Can-Reads-Indies #3: Wild Geese by Martha Ostenso

I wasn't the only reader for whom the highlight of Canada Reads 2009 was Michel Tremblay's The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant, which was a book that we all should have read, that we were all better for having read, but I would never have picked it up otherwise. Sometimes the prospect of looking to the past for books we should have read is a bit like contemplating getting into Joyce Carol Oates-- where do we start, and how would we ever be able to stop?

I wasn't the only reader for whom the highlight of Canada Reads 2009 was Michel Tremblay's The Fat Woman Next Door is Pregnant, which was a book that we all should have read, that we were all better for having read, but I would never have picked it up otherwise. Sometimes the prospect of looking to the past for books we should have read is a bit like contemplating getting into Joyce Carol Oates-- where do we start, and how would we ever be able to stop?So it's nice to get a bit of guidance, and I feel the very same about Martha Ostenso's Wild Geese, which I'd never even heard of until I encountered NCL obsessive Melanie Owen online. In its day (1925), Wild Geese was a bestseller, was even made into a film, and heralded a new direction in Canadian fiction (though I'm not sure who followed in that direction-- Sinclair Ross? Hugh MacLennan? See, with this early stuff, my knowledge is very sketchy. I read Ernest Buckler once. Anyway...)

Wild Geese takes place in a rural community in northern Manitoba. Schoolteacher Lind Archer arrives to board with the Gare family, and quickly realizes that something is amiss-- somehow Caleb Gare has got his wife and children stuck under his thumb, and they're terrified of defying him. He works them like animals on the farm, keeps them isolated from the community, wields his power with brute force, and he takes care to bully and blackmail his neighbours on the side. Caleb has met his match in daughter Judith, however, powerful in spirit and body (she reminded me so much of Jo March), who is desperate to get away from her tyrannical father and is inspired by Lind to finally do so.

"Powerful" is overused as an adjective to describe a book, and I wish I could coin a new way to describe exactly what Wild Geese does to its readers. The book was engrossing in way I've not very often experienced-- closest comparison is my Andrew Pyper nightmares. Usually I read at a distance from novels, keeping the literary world and my own sensibly divided, but parts of Wild Geese crept into my consciousness. I read the chapter where Lind comes home in the dark and keeps making out creepy shadows and shapes behind her and around her, and I read this in the middle of a sunny afternoon, but I was freaked out. Similar, the conclusion-- I absolutely couldn't take it anymore and had to skip to the final pages to prevent a heart attack.

I also had such strong feelings about Caleb's wife, Amelia Gare. Caleb had married her aware that she'd previously had a child out of wedlock, and he uses this knowledge to control her throughout their marriage. The control, however, comes from Amelia's fear that Caleb would tell her son of his background (which he had been blissfully unaware of, told he was well-born, by the priests who'd raised him). Amelia's feelings for this son are so strong that she is willing to sacrifice her other children for him, the spirited Judith in particular, and this absolutely enraged me as I read. Perhaps more than Caleb did himself.

Caleb Gare is a fascinating character, soft-spoken in the creepiest way possible. At first, I thought he was simplistic, his purposes far too blatent-- Ostenso has him rubbing his hands together whilst surveying his land, wondering, "what the occasion would be, if it came to that, which would finally force him to play his trump card, as he liked to call it... He firmly believed that knowledge of Amelia's shame would keep the children indefinitely to the land..."

But when I saw him interacting with members of the community with similar schemes and tricks, manipulating and blackmailing, this behaviour with his family began to seem very consistent. Caleb Gare is a completely unsympathetic character, and I am not sure this equals a lack of complexity in his moral make-up. We are tuned these days to see such characters as poorly drawn, but I'm not sure now. Ostenso has Caleb Gare making sense: everything he did was for his own gain-- he worked his family hard so that he wouldn't have to work as hard himself or pay anyone else to do so, he worked his neighbours to get his hands on their land and therefore expand his own power. He delighted in this power too, perhaps his only source of joy, save for his land, and there is a vital relationship between the two.

In addition to his sheer meanness, we are supposed to see Caleb Gare's connection to his land as part of the motivation for his behaviour, but this is a given, not wholly explored. Which I've found in a lot of books, actually. It's taken for granted that land can make a man do certain things, but I'm often left wondering exactly why. Ostenso does show that Gare (through using his family as slaves) is able to reap a bounty from the harsh northern lands in a way his neighbours are unable to do-- that his domination extends even to the crops he commands. But I would have liked to know more about why Caleb feels the way he does about his land. It could be, however, that we don't know how he feels the feels and thinks very little beyond his conniving. That Caleb is absolutely spiritually bankrupt, and this does seem to be the case.

Ostenso's treatment of the landscape itself is vivid, of the inhabitants, and elements of Norse mythology informing their lives lends to the spooky treatment. The depiction of the land is also remarkable for the way in which the delicate, lovely and elegant Lind Archer's contrast with it. Her presence as a foreign object in this strange brutal place is the catalyst for all that transpires, and also gives us a perspective on the Gares from without, which is most illuminating. Her relationship with Mark Jordan, another recently transplant (who is Amelia Gare's illeg. son! This is not a spoiler, however, as we're told from the outset) provides also provides necessary relief from the brutality of all other human relations.

In short, unlike much Canadian prairie fiction, Wild Geese didn't make me want to kill myself.

From about midway in, I was rapt by this book, but there is one big reason why it won't be top of my list of Canada Reads: Independently picks. Primarily, the way in which the prose of Wild Geese manages to sometimes reads like an undergraduate essay on Wild Geese. Such as when Lind Archer says, "That's what's wrong with the Gares. They all have a monstrously exaggerated conception of their duty to the land-- or rather to Caleb, who is nothing but a symbol of the land." There is something particularly ubsubtle about the book's structures, particularly when compared to the complexity of a book like Century.

Still though, it's a riveting read, pushes its language and imagery in challenging directions, is unafraid to shy away from uncomfortable or even horrifying situations, and tackles female sexuality in a beautiful way. (Yes-- Canadian fiction in which the woman gets to be the horse, for once.) If this book is underread, it should be no longer.

Canada Reads Independently Rankings:

1) Hair Hat by Carrie Snyder

2) Century by Ray Smith

3) Wild Geese by Martha Ostenso

As long as it's not dangerous

"The Cambridge History of English Literature was my constant companion, and it became infused with my cigarette smoke as I plodded through the pages. Almost all my women friends were smokers, some using cigarettes to affect a social ease and grace; others, more dependent upon them, becoming chain smokers. I myself was convinced that without a cigarette in my mouth I could neither study nor exercise any creativity. All unconscious of future revelations about nicotine, my mother would say to me, 'Why not-- as long as it's not dangerous.' And so I smoked my way through the Cambridge History of English Literature." --from Old Books, Rare Friends: Two Literary Sleuths and Their Shared Passion by Leona Rostenberg and Madeleine Stern (which is wonderful)

Tuesday, February 09, 2010

Things India Knight likes

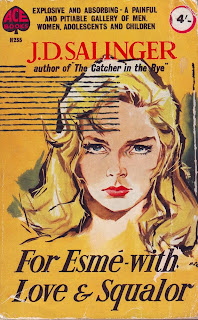

Writer India Knight has long been included on a list of things I like, but today she has managed to drive me mad with ecstasy via her blog Things I like. Now with Search Button. In particular, her things to read tag, from which I found myself directed to Curious Pages, The Reading Weekend and Missed Connections. Pre-Miffy Bruna-- amazing. I now want a beautiful house in Brussels, a giant owl, and to be Tavi. Such a wonderful catalogue of marvelous things. Image from this post-- turns out Salinger's covers weren't always so enigmatic.

Writer India Knight has long been included on a list of things I like, but today she has managed to drive me mad with ecstasy via her blog Things I like. Now with Search Button. In particular, her things to read tag, from which I found myself directed to Curious Pages, The Reading Weekend and Missed Connections. Pre-Miffy Bruna-- amazing. I now want a beautiful house in Brussels, a giant owl, and to be Tavi. Such a wonderful catalogue of marvelous things. Image from this post-- turns out Salinger's covers weren't always so enigmatic.

Monday, February 08, 2010

Canada Reads 2010: Independently UPDATE 4

I'm almost through Wild Geese, and though I've enjoyed it, it probably won't knock the other two I've read out of the top two spots. A review will be posted in a day or two. Julie Forrest posts her review of Hair Hat: "[W]hen it comes to Alice Munro-esque stories about ordinary people, I’m hard to impress. Hair Hat impresses". Buried in Print republishes an old Hair Hat review. Steven Beattie does too, though his is less complimentary (and I would suggest a reread and cessation of dirty tricks). WriterGuy on Moody Food: he was put off by the prose at times, but found the narrative compelling. My friend Bronwyn has reported that Century is her favourite book of the bunch. My husband Stuart liked Moody Food so much that he emailed Ray Robertson to tell him. In a recent conversation, writer Amy Jones reported she'd just started Ray Smith's Century and that she also was impressed. American Librarians' blog Librations is jealous of Canada Reads and the copies it has inspired (which is us and the National Post's). And I was fascinated by Charlotte Ashley's post which used more of her "uncontrolled bookselling research" to assess the New Canadian Library's rebranding: in two years, outside the context of university course lists, her bookstore has only ever sold two NCL titles and one of those was to Charlotte Ashley for our project's Wild Geese.

I'm almost through Wild Geese, and though I've enjoyed it, it probably won't knock the other two I've read out of the top two spots. A review will be posted in a day or two. Julie Forrest posts her review of Hair Hat: "[W]hen it comes to Alice Munro-esque stories about ordinary people, I’m hard to impress. Hair Hat impresses". Buried in Print republishes an old Hair Hat review. Steven Beattie does too, though his is less complimentary (and I would suggest a reread and cessation of dirty tricks). WriterGuy on Moody Food: he was put off by the prose at times, but found the narrative compelling. My friend Bronwyn has reported that Century is her favourite book of the bunch. My husband Stuart liked Moody Food so much that he emailed Ray Robertson to tell him. In a recent conversation, writer Amy Jones reported she'd just started Ray Smith's Century and that she also was impressed. American Librarians' blog Librations is jealous of Canada Reads and the copies it has inspired (which is us and the National Post's). And I was fascinated by Charlotte Ashley's post which used more of her "uncontrolled bookselling research" to assess the New Canadian Library's rebranding: in two years, outside the context of university course lists, her bookstore has only ever sold two NCL titles and one of those was to Charlotte Ashley for our project's Wild Geese.

Sunday, February 07, 2010

Furnishing a room

Our house is currently in a state of upheaval as we begin the process of moving the baby into her own room. We've got a faint hope that it might help her sleep better, and after eight months of enjoying having her close, we want our room back. And no doubt she'll be joining us there most nights anyway (and yay for reluctant co-sleeping, which is much better than being awake).

Our house is currently in a state of upheaval as we begin the process of moving the baby into her own room. We've got a faint hope that it might help her sleep better, and after eight months of enjoying having her close, we want our room back. And no doubt she'll be joining us there most nights anyway (and yay for reluctant co-sleeping, which is much better than being awake).Baby will be moving into the spare-room/ office/ library, however, so the books have had to migrate living-room-ward. Which at first I was sad about, that the books would be losing a room of their own, but now having them out in the world again, I realize that I've missed them. How little I visited our library, unless I had a reason to, and how nice the spines are just to stare at, and the journeys they could take me on from my seat here in the gliding chair.

And I realize that books have been missing from this room all along. It's so nice to be back among them. The aesthetic effect of their various colours and heights. How the walls were empty before, and the floor just too wide, and how the built-in shelf beside the fireplace was wasted before now. It's true, they do-- they furnish a room! And joyfully, because televisions don't, we're getting rid of ours, so just excuse the focal point in the photo in the meantime.

And I realize that books have been missing from this room all along. It's so nice to be back among them. The aesthetic effect of their various colours and heights. How the walls were empty before, and the floor just too wide, and how the built-in shelf beside the fireplace was wasted before now. It's true, they do-- they furnish a room! And joyfully, because televisions don't, we're getting rid of ours, so just excuse the focal point in the photo in the meantime.

Thursday, February 04, 2010

News and news

My goodness, haven't things around here been anticlimactic since Family Literacy Week ended. You want to know the best thing about Family Literacy Week though? That it was totally made up. True story. Family Literacy DAY was the real deal, but I thought one day wasn't enough, so I dragged it out for another six, and then people started walking around thinking it was legitimate. At least two people that I know of! This is certainly not the first rumour I ever started, but it's probably one of the more productive ones. It was a very good week, and I am so grateful for everyone who contributed. And I am sorry if I misled you...

My goodness, haven't things around here been anticlimactic since Family Literacy Week ended. You want to know the best thing about Family Literacy Week though? That it was totally made up. True story. Family Literacy DAY was the real deal, but I thought one day wasn't enough, so I dragged it out for another six, and then people started walking around thinking it was legitimate. At least two people that I know of! This is certainly not the first rumour I ever started, but it's probably one of the more productive ones. It was a very good week, and I am so grateful for everyone who contributed. And I am sorry if I misled you... Since then, however, I've been busy with deadlines, and preparations, plus I've been exhausted thanks to this baby whose sleep habits are beyond appalling. Thanks to all of this (save the baby), however, we are on the cusp of some very exciting things. Amy Jones is coming over tomorrow afternoon for her interview (and I've baked scones for the occasion.) I'm starting Wild Geese tomorrow, and my Canada Reads Independently update will be posted this weekend. And sometime soon I'll be rolling out my gorgeous new website over at my own domain! I hope you'll all adjust your links accordingly, and follow me there. Stay tuned for the official announcement...

Since then, however, I've been busy with deadlines, and preparations, plus I've been exhausted thanks to this baby whose sleep habits are beyond appalling. Thanks to all of this (save the baby), however, we are on the cusp of some very exciting things. Amy Jones is coming over tomorrow afternoon for her interview (and I've baked scones for the occasion.) I'm starting Wild Geese tomorrow, and my Canada Reads Independently update will be posted this weekend. And sometime soon I'll be rolling out my gorgeous new website over at my own domain! I hope you'll all adjust your links accordingly, and follow me there. Stay tuned for the official announcement...Of course, lately I've also been reading. Barbara Pym's A Glass of Blessings, and Canadian Notes and Queries. From the latter, I especially enjoyed Clark Blaise's story "In Her Prime", Seth on Canadian Cartoonist Doug Wright, Ray Robertson (of the Canada Reads Independently Moody Food) "In Anticipation". I've been reading Sylvia Plath's The Bed Book with illustrations by Quentin Blake, and The Tree of Life by Peter Sis on the recommendation of Genevieve Cote. I've been reading Annabel Lyon on writing and motherhood. Mark Sampson on email interviews. Steven Beattie's "The problem of sustained reading in a distracted society". Meli-Mello celebrated Family Literacy Week also last week, and this week she's talking about toys.

Tuesday, February 02, 2010

Embracing the Ego? A reevaluation

I changed my mind, sort of. After thinking a lot about why we should read, and deciding (along with Fran Lebowitz and Diana Athill) that we should read in order to escape ourselves, I realize that reading is not so simple. That here I sit spouting nonsense about what reading is for from a position of enormous privilege (read: literacy, internet access, enough of my immediate needs met that I have time to sit here spouting nonsense) about what reading is for, but I'm missing most of the story.

It is annoying, I think, when people who spend most of their time gazing into mirrors anyway choose to see literature also as a reflective surface. This, of course, is what Fran Lebowitz called "a philistine idea... beyond vulgar." But I'm starting to realize that we're only talking about a fraction of the population when we generalize in this way. There are people with real problems (and I'm sorry quarter-life-crisis-ers, but I'm not talking about you!) for whom literature would be a most productive therapy, and also for whom this kind of personal engagement might be their gateway into books (which is splendid!). For anyone to devalue this kind of reading is incredibly patronizing, and stupid. (And perhaps to devalue any kind of reading is patronizing and stupid too).

I am learning more about the work done by Literature For Life, about their Book Circles whose participants have often never read an entire book before . The first book their groups read is The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah, selected for being plot-driven and for the way in which the story might relate to readers' lives. Confidence grows from just one book, and so does interest, so that someone who has only read one book before might go and pick up another. So that, yes, a reader is born, but also these readers can begin to address their own problems with the advantage of some distance, that they gain access to a new way of examining and understanding their own experience. Language becomes a tool for self-expression. Subsequent books read become more challenging, but all of them connect back to the readers' experience somehow, and I see now how much is right with that.

Perhaps what I find most fascinating about the Lit. for Life Book Circles (whose participants are pregnant and parenting teenage mothers) is that these communities of readers approach literature from a wholly different angle than what I'm used to. We all like to go on and on about the use-value of literature, which for most of us is theoretical, but these readers put those theories in motion. These girls whose lives are changed by the power of one book-- they are a testament to what literature can do. Those of us who take books for granted can certainly learn something from that.

Anyway, there will be more learning to come. I'm going to be doing some work with Literature for Life over the coming months, and I look forward to sharing those experiences here.

It is annoying, I think, when people who spend most of their time gazing into mirrors anyway choose to see literature also as a reflective surface. This, of course, is what Fran Lebowitz called "a philistine idea... beyond vulgar." But I'm starting to realize that we're only talking about a fraction of the population when we generalize in this way. There are people with real problems (and I'm sorry quarter-life-crisis-ers, but I'm not talking about you!) for whom literature would be a most productive therapy, and also for whom this kind of personal engagement might be their gateway into books (which is splendid!). For anyone to devalue this kind of reading is incredibly patronizing, and stupid. (And perhaps to devalue any kind of reading is patronizing and stupid too).

I am learning more about the work done by Literature For Life, about their Book Circles whose participants have often never read an entire book before . The first book their groups read is The Coldest Winter Ever by Sister Souljah, selected for being plot-driven and for the way in which the story might relate to readers' lives. Confidence grows from just one book, and so does interest, so that someone who has only read one book before might go and pick up another. So that, yes, a reader is born, but also these readers can begin to address their own problems with the advantage of some distance, that they gain access to a new way of examining and understanding their own experience. Language becomes a tool for self-expression. Subsequent books read become more challenging, but all of them connect back to the readers' experience somehow, and I see now how much is right with that.

Perhaps what I find most fascinating about the Lit. for Life Book Circles (whose participants are pregnant and parenting teenage mothers) is that these communities of readers approach literature from a wholly different angle than what I'm used to. We all like to go on and on about the use-value of literature, which for most of us is theoretical, but these readers put those theories in motion. These girls whose lives are changed by the power of one book-- they are a testament to what literature can do. Those of us who take books for granted can certainly learn something from that.

Anyway, there will be more learning to come. I'm going to be doing some work with Literature for Life over the coming months, and I look forward to sharing those experiences here.

Foolscap is awkward to read in bed

"'Will she expect a comfortable bed?' Rodney asked. 'Oughtn't we to break her into the world gradually?'

'I don't see what difference it makes,' I said.

'Wilmet, have you thought what books to put by her bed?' asked Sybil. 'You must make a careful choice.'

'I suppose some anthologies of poetry and good novels by female authors,' I said. 'Not devotional books, obviously.'

'We have just completed an interesting report on the Linoleum Industry,' said Rodney. 'I could let her have a cyclostyled copy-- the pages are bound together.'

'Foolscap is awkward to read in bed,' said Sybil. 'Arnold has just published a paper in one of the archeological journals-- that's a handy size for night reading and there are some excellent drawings of pottery fragments done by an invalid lady who lives in Dawlish.'"-- from A Glass of Blessings by Barbara Pym(!)

'I don't see what difference it makes,' I said.

'Wilmet, have you thought what books to put by her bed?' asked Sybil. 'You must make a careful choice.'

'I suppose some anthologies of poetry and good novels by female authors,' I said. 'Not devotional books, obviously.'

'We have just completed an interesting report on the Linoleum Industry,' said Rodney. 'I could let her have a cyclostyled copy-- the pages are bound together.'

'Foolscap is awkward to read in bed,' said Sybil. 'Arnold has just published a paper in one of the archeological journals-- that's a handy size for night reading and there are some excellent drawings of pottery fragments done by an invalid lady who lives in Dawlish.'"-- from A Glass of Blessings by Barbara Pym(!)

Sunday, January 31, 2010

Meet the Smiths

I've got a family of Smiths on my bookshelf. Probably you do too. Mine are diverse but an excellently harmonious bunch. There's Ali, of course, of The Accidental and Girl Meets Boy. And then Alison, of the poetry collection Six Mats and One Year. Next is Betty, who wrote A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Beside her is Ray, then Russell, and Zadie, who have brought to the library Century, Muriella Pent and White Teeth/On Beauty, respectively.

I've got a family of Smiths on my bookshelf. Probably you do too. Mine are diverse but an excellently harmonious bunch. There's Ali, of course, of The Accidental and Girl Meets Boy. And then Alison, of the poetry collection Six Mats and One Year. Next is Betty, who wrote A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Beside her is Ray, then Russell, and Zadie, who have brought to the library Century, Muriella Pent and White Teeth/On Beauty, respectively.This is the largest clan in my library, save for the Mitfords who don't actually count because they're really sisters. And I'm not sure if this bunch is alike or unhappy in their own way, but I like how their jackets rub together anyway.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Raise high the roofbeam carpenters

Phoebe Caulfield was Holden's nine-year old sister, plucky as a red-headed orphan, just lacking appropriate pigmentation and tragedy. Even Holden would affirm that, "if you don't think she's smart, you're mad."

Pheobe was a writer, composing the stories of "Hazel Weatherfield" in her multiple notebooks. As an actor, she was ecstatic to have the largest part in her class play, even if it involved playing Benedict Arnold. "Elephants knock[ed] her out." Phoebe Caulfield was a force to be reckoned with, pouring ink down the windbreaker of anyone who dare cross her path and she could recite Robbie Burns on command.

She was also a realist. While her brother Holden tried to deny his bleak reality, Phoebe made a point of thrusting the thing in his face. Not allowing him the luxury of his skewed perspective, sick of tirades about phoniness, she says bluntly, "You don't like anything." In contrast, Pheobe herself was able to make the best of her difficulties. Holden's drunken shattering of record he'd bought for her failed to hinder her enthusiasm for the gift: "'Gimme the pieces,' she said. 'I'm saving them.'"

A beacon in her brother's lonely existence, Phoebe's love makes clear Holden's real emotional capacity and the depth of his troubles. Upon learning that he'd been expelled from yet another school, hers is the first display of genuine, grounded concern anyone shows him. Her maturity outmatches Holden's, and his tender feelings towards her highlight his own vulnerability.

In Phoebe, Holden also sees the innocence he has lost, but elsewhere in Salinger's oeuvre is evidence that Phoebe Caulfield was wise rather than naive, and that her wisdom beyond her years ("Old Phoebe") might never have disappeared. I like to think that if Salinger had continued the saga of the Caulfield family, Phoebe would have grown up to be someone much like Boo Boo Glass.

Of course, the details of Salinger's salacious personal life widely reported him as something of a letch, and his stories contain their share of one-dimensional female characters. But he knew something about women, or perhaps something about sisters is more what I mean.

Boo-Boo appears in the background of Salinger's Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters. She also makes an appearance in "Down at the Dinghy" from Nine Stories, in which "[h]er general unprettiness aside," writes Salinger, "she was a stunning and final girl." Ever capable, Boo-Boo flew with the Woman's Air Force in World War Two, bravely tackled anti-Semitism in her marriage to a Jewish man, and mothered her young son with the same insightful sensitivity Phoebe provides to her brother Holden.

In a tortured world of Seymour and perfect days for bananafish, Boo-Boo stands on the side of justice, for all things bright and good, however much in vain. And I am insistent upon optimism, so for me, it is her spirit that pervades Salinger's best writing and makes me love it so. Her presence in Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters consists solely of a note left on the bathroom mirror of her brothers' New York apartment. "'Raise high the roofbeam carpenters... Please be happy happy happy. This is an order. I outrank everyone on the block."

(an earlier version of this piece appeared in the independent weekly on September 6 2001.)

Pheobe was a writer, composing the stories of "Hazel Weatherfield" in her multiple notebooks. As an actor, she was ecstatic to have the largest part in her class play, even if it involved playing Benedict Arnold. "Elephants knock[ed] her out." Phoebe Caulfield was a force to be reckoned with, pouring ink down the windbreaker of anyone who dare cross her path and she could recite Robbie Burns on command.

She was also a realist. While her brother Holden tried to deny his bleak reality, Phoebe made a point of thrusting the thing in his face. Not allowing him the luxury of his skewed perspective, sick of tirades about phoniness, she says bluntly, "You don't like anything." In contrast, Pheobe herself was able to make the best of her difficulties. Holden's drunken shattering of record he'd bought for her failed to hinder her enthusiasm for the gift: "'Gimme the pieces,' she said. 'I'm saving them.'"

A beacon in her brother's lonely existence, Phoebe's love makes clear Holden's real emotional capacity and the depth of his troubles. Upon learning that he'd been expelled from yet another school, hers is the first display of genuine, grounded concern anyone shows him. Her maturity outmatches Holden's, and his tender feelings towards her highlight his own vulnerability.

In Phoebe, Holden also sees the innocence he has lost, but elsewhere in Salinger's oeuvre is evidence that Phoebe Caulfield was wise rather than naive, and that her wisdom beyond her years ("Old Phoebe") might never have disappeared. I like to think that if Salinger had continued the saga of the Caulfield family, Phoebe would have grown up to be someone much like Boo Boo Glass.

Of course, the details of Salinger's salacious personal life widely reported him as something of a letch, and his stories contain their share of one-dimensional female characters. But he knew something about women, or perhaps something about sisters is more what I mean.

Boo-Boo appears in the background of Salinger's Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters. She also makes an appearance in "Down at the Dinghy" from Nine Stories, in which "[h]er general unprettiness aside," writes Salinger, "she was a stunning and final girl." Ever capable, Boo-Boo flew with the Woman's Air Force in World War Two, bravely tackled anti-Semitism in her marriage to a Jewish man, and mothered her young son with the same insightful sensitivity Phoebe provides to her brother Holden.

In a tortured world of Seymour and perfect days for bananafish, Boo-Boo stands on the side of justice, for all things bright and good, however much in vain. And I am insistent upon optimism, so for me, it is her spirit that pervades Salinger's best writing and makes me love it so. Her presence in Raise High the Roofbeam Carpenters consists solely of a note left on the bathroom mirror of her brothers' New York apartment. "'Raise high the roofbeam carpenters... Please be happy happy happy. This is an order. I outrank everyone on the block."

(an earlier version of this piece appeared in the independent weekly on September 6 2001.)

Friday, January 29, 2010

Celebrating literacy in general, and those who promote it

For obvious reasons, this is my favourite page in The Baby's Catalogue. Oh, children's books. They're as good as any book, but they've got pictures. And it has been a delight to celebrate them this week, to celebrate Family Literacy, and to find out that such a celebration is so contagious. That children's books are made to be shared.

For obvious reasons, this is my favourite page in The Baby's Catalogue. Oh, children's books. They're as good as any book, but they've got pictures. And it has been a delight to celebrate them this week, to celebrate Family Literacy, and to find out that such a celebration is so contagious. That children's books are made to be shared.Of course, we're preaching to the choir here. Anyone who'd be reading this blog in the first place (except for whatever curious person arrived searching for "sex with pickles") is probably well aware of the importance of family literacy. I bet we were all read to as children, that we read to any children we have, and that we even read to children we don't have.

And all of this, of course, is a luxury. Family Literacy Day is sponsored by ABC Canada, which promotes adult literacy through a wide variety of programs. We are fortunate that in Canada, illiteracy is rare, but less rare (and harder to acknowledge) are low literacy skills, which are experienced by 4 out of 10 Canadians. The implications of this are enormous, in particular at the family level, and at the workplace level, and through their programs, ABC Canada aims to provide adults access to the learning skills they require.

Another organization doing wonderful work for literacy is the Children's Book Bank in Toronto, which provides children in the Regent Park neighbourhood with free books and a terrific atmosphere in which to enjoy them. The space is absolutely beautiful, like the best children's bookstore you can imagine, and the books (albeit secondhand) are in good shape, excellently organized. It's a place that respects itself, and the kids sense that, and feel better about themselves for just being there, and their pleasure at choosing books of their own is absolutely palpable. They also often come accompanied by their parents, many of whom end of learning English literacy skills from the books their kids bring home from the Book Bank. The Children's Book Bank is a fantastic innovation, and I'd recommend it for anyone who is looking to get rid of good quality used children's books, or as a good recipient for a book drive.

A final organization in Toronto that I'm just starting to learn about is Literature for Life, which promotes reading to groups of pregnant or parenting teenage mothers, and publishes a magazine by these women and for them. It's an amazing idea, whereby not only do these women learn how reading enriches their lives, but they gain the skills to pass a love of reading on to their children.

***

Finally, I want to share my favourite Family Literacy Resources. Australian writer Mem Fox has an excellent website, including her instructions for reading aloud and her Ten read-aloud commandments (1. Spend at least ten wildly happy minutes every single day reading aloud.)

And more recently, I've fallen in love with Canadian author Sheree Fitch's website. Sheree Fitch is an inventor of words, and she's made up one called "thrival", which is as important as "survival", and is what literacy is necessary for. Read her excellent essay here. Her own list of literacy resources is here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)